Economists used to believe that human beings are fundamentally rational creatures.

They based their models on the assumption that – when faced with a trade-off and armed with complete and accurate information – people choose the option that maximizes their well-being.

It’s unclear if these economists had ever actually met a human being.

We procrastinate and eat junk food and don’t save for retirement.

We miss deadlines and say yes to things we don’t have time for and stay in careers that make us miserable.

We complain about not having enough time and then fail to use the time we do have wisely.

In short, we're kind of bad at making good decisions.

In the 1970s, Israeli psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman turned the field of economics upside down by observing what, in hindsight, seems obvious: people act against their rational self-interest all the time. But where many people saw random quirks of human psychology, Tversky and Kahneman saw patterns.

Over decades of research and experiments, the pair found that we all tend to make the same mental mistakes, and we make them over and over again. Humans are irrational, yes. But they are, as psychologist Dan Ariely named his book on the subject, predictably irrational. Which is very good news for us.

There’s not much we can do about random irrationality, but predictable irrationality can be studied, cataloged, and maybe – just maybe – avoided. Tversky and Kahneman’s work sparked a whole new field of study called behavioral economics to do just that. To date, behavioral economists have identified over 100 of these persistent mental errors – called cognitive biases – that distort our decision-making in all sorts of ways every day.

This being a blog about productivity, we’re going to focus on the seven cognitive biases that have the biggest impact on the way we spend our time, prioritize our tasks, and achieve (or fall short of) our goals – with concrete strategies to avoid them:

- The Mere Urgency Effect

- The Zeigarnik Effect

- The Planning Fallacy

- The Sunk Cost Fallacy

- Present Bias

- Complexity Bias

- Hedonic Adaptation

1. The Mere Urgency Effect a.k.a. Why we let unimportant tasks take over our days

The Mere Urgency Effect describes our tendency to prioritize tasks we perceive as time-sensitive over tasks that aren’t time-sensitive, even when the rewards of the non-time-sensitive task are objectively greater. In other words, urgency trumps importance every time.

This cognitive bias explains why, despite our best intentions, we get sucked into email at the expense of more impactful work. Email invariably feels urgent – there’s always someone waiting for a reply. In contrast, our most important goals are often far off. There are no immediate consequences to putting them off until tomorrow.

Interestingly, research shows that people who perceive themselves as being generally busy are even more likely to fall victim to the Mere Urgency Effect. Those who feel like they have the least amount of time are the least likely to use it well.

What you can do about it:

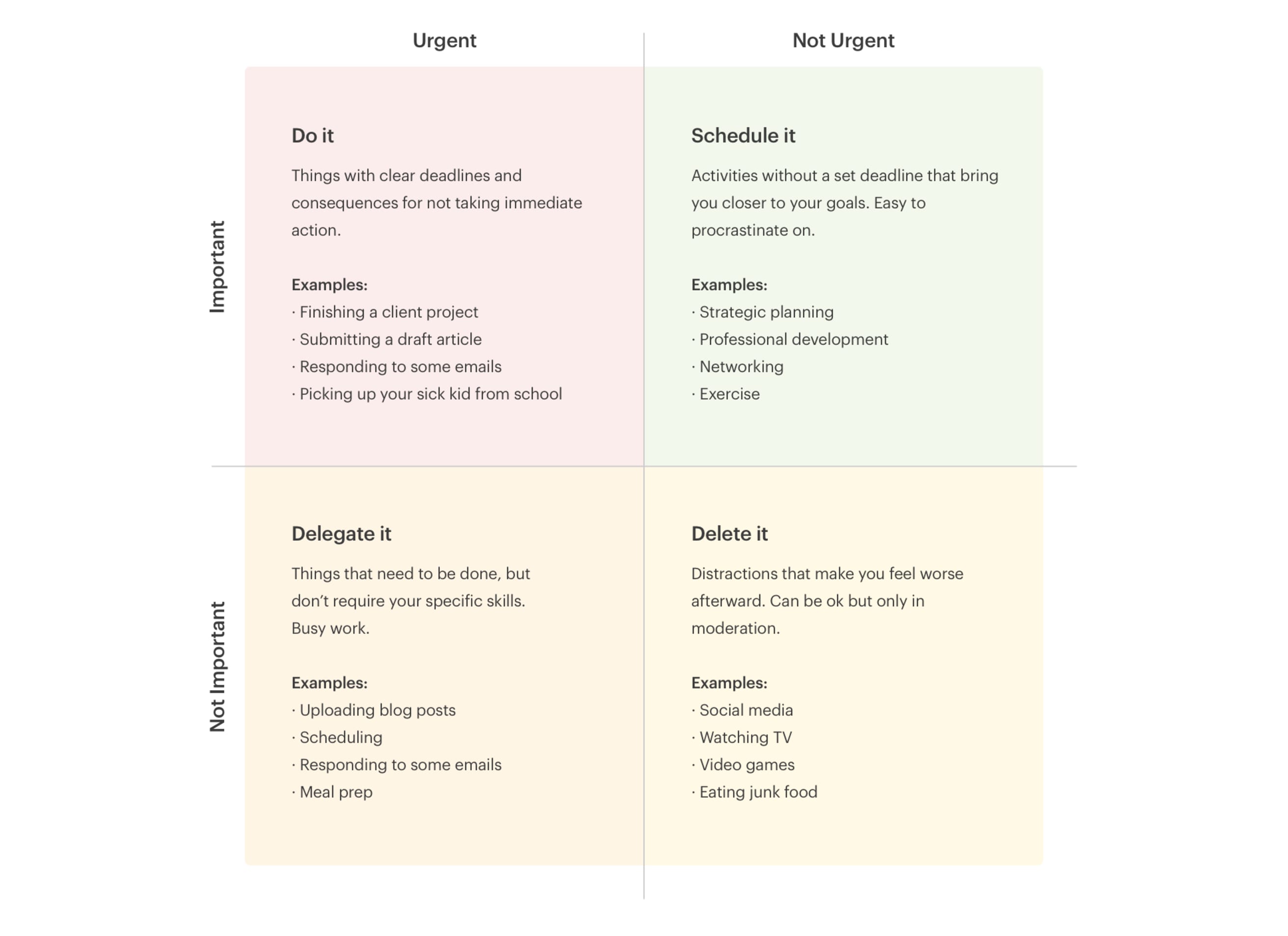

Use the Eisenhower Matrix to prioritize your tasks. The Eisenhower Matrix is a framework for classifying tasks as urgent/not urgent and important/not important. The matrix helps you decide what to do with a task depending on which quadrant it falls into.

Set aside your most productive 2-4 hours each day for your most important work. Dedicate your most productive hours to your most important work. Block that time off on your calendar so you can focus without interruptions.

Only answer emails at certain times of day. Set aside specific time blocks for answering email. For example, at 12pm-12:30 and 4pm-5pm. Don’t let email bleed into other time of your day. If you find yourself opening your inbox outside of your email time blocks, use an app blocker like Freedom to lock yourself out at certain times of the day. Alternatively, use an inbox management tool like Mailman that batches incoming mail and delivers it at hourly intervals, a set number of times per day, or at specific times.

Give your important tasks a deadline. It’s nearly impossible to trick yourself into keeping an arbitrary deadline you’ve set for yourself, so find a way to commit to an external deadline, even if you’re just telling a friend.

More reading if you're interested:

How Busyness Leads to Bad Decisions

Avoid the “Urgency Trap” With the Eisenhower Matrix

The Complete Guide to Time Blocking

2. The Zeigarnik Effect a.k.a. Why we can’t stop thinking about everything we need to get done

In the 1920s, Russian psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik observed an odd thing. While dining out, she was impressed by the complex orders the wait staff was able to remember at one time. Yet, as soon as the bill was paid, the wait staff forgot completely what the orders were. This observation gave rise to the study of what would become known as the Zeigarnik Effect.

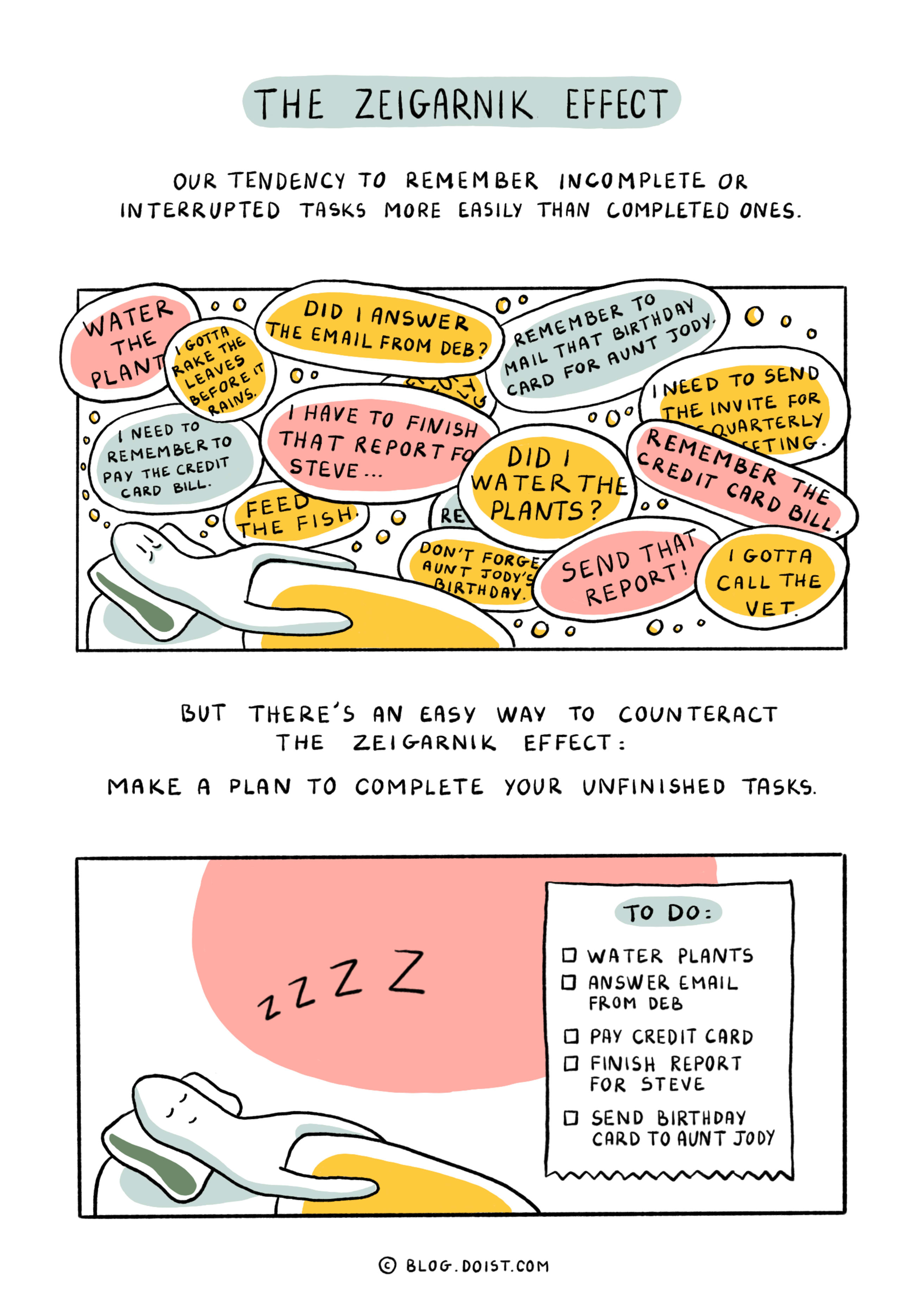

The Zeigarnik Effect refers to our tendency to remember incomplete or interrupted tasks better than completed ones. At first glance the Zeigarnik Effect can seem like a handy adaptation: It’s good to remember the things we need to do, and it’s a positive thing to want to finish the things we start. The problem when it comes to our productivity is two-fold:

First, each incomplete task your brain reminds you about takes up a bit of your attention, splitting your focus and making it harder to concentrate on whatever you’re currently working on. One study found that people who were interrupted during a task performed worse on a subsequent task than those who were allowed to complete the first task before starting the second one.

Second, even if we manage to physically disconnect from work, the Zeigarnik Effect ensures that our unfinished tasks follow us home. They intrude on our family dinners, our vacations, our weekends, and our sleep. There will always be work left to do. We need a way to find relief from the Zeigarnik Effect so we can mentally disconnect in our hours away from work.

The good news is you don’t have to actually complete all of your tasks in order to feel mental relief from the Zeigarnik Effect. Research shows that simply making a plan to finish your incomplete tasks can snooze your brain’s automatic reminders.

What you can do about it:

Write your tasks down. Your brain is a terrible filing system. Instead of keeping tasks in your head, make a habit of writing them down as soon as they come to you. Keep a digital task manager like Todoist on your computer and phone, so you’ll always have it handy to jot down a new to-do.

Have a system for organizing and regularly reviewing your tasks. Your system won’t work if your brain doesn’t trust that it’s accurate and up-to-date. Create rituals for planning your day and week so your brain can trust you’re working on the right things at the right time and can worry about everything else later.

Have an end of work shutdown ritual. Make a plan for tomorrow before you end the work day so your unfinished tasks don’t linger in your mind after-hours.

Find a small way to just get started. The Zeigarnik Effect can also be used to our advantage. When you find yourself putting off a particularly big or difficult task, identify a very small first step you can take. The simple act of starting can trigger your brain to want to keep going to the end.

Don’t forget to look back at how far you’ve come. Another negative side effect of the Zeigarnik Effect is that we quickly forget everything we’ve already accomplished. Don’t forget to look back at your completed tasks during a weekly review to celebrate what you’ve already

More reading if you're interested:

The Psychology of the To-Do List – Why Your Brain Loves Ordered Tasks

The Weekly Review: A Productivity Ritual to Get More Done

The Complete Guide to Planning Your Day

3. The Planning Fallacy a.k.a. Why we miss deadlines

The Planning Fallacy refers to our tendency to underestimate the time it will take to complete a future task despite knowing that similar tasks have taken longer in the past. Homeowners underestimate how much time renovations will take. Writers underestimate the amount of time they’ll need to complete a novel. Product managers underestimate how long a new feature will take to build. Elon Musk misses Tesla production timeline after Tesla production timeline. (When asked about his penchant for giving wildly inaccurate predictions, Musk replied "People should not ascribe to malice that which can easily be explained by stupidity.”)

Worse still, multiple studies show that we underestimate timelines even when we know we’re likely to underestimate timelines.

The Planning Fallacy can be a great thing. How many projects would we never have taken on if we had an accurate understanding of how much work and time would be required at the start? Sometimes, ignorance is bliss. But most of the time, committing to overly optimistic deadlines just leads to a lot of unnecessary stress and guilt.

We can’t meet deadlines, but we can’t get anything done without them (see the Mere Urgency Effect above), so how do we learn to live with them?

What you can do about it:

Break projects down into smaller parts and estimate how long each will take. The more granular you can be in your project planning, the more realistic your time estimates tend to be. It’s easy for me to say, “Sure, I can absolutely get that draft to you in 2 days”, but when I break down how many words per hour that would require, it becomes obviously unrealistic.

Pad your schedules more than you think you need to. Whatever you think is a reasonable project timeline, pad the schedule with 20%. As you’re planning your week, pretend Friday (20% of the work week) doesn’t exist. If you get to Friday with everything complete, great! You can spend that time learning or working on a side project or getting ahead on the next thing. But more likely than not, the work you planned for four days will end up spilling over into the fifth. It’s better to plan for it than be surprised by it.

Use historical data to make better predictions. Start tracking the time it takes you to actually complete things, and use that historical data to make more accurate predictions. Don't fool yourself into thinking you’ll be able to finish it faster next time. Use a time tracking tool like Toggl that integrates with several task managers, including Todoist, so you can start your timer right from your task lists.

Limit the scope of work. At Doist, we work in four-week project cycles. While we’ve gotten better at planning our work over the years, projects can still fall behind. Instead of extending the timeline, our project squads have started reducing the scope of work mid-cycle. This way, even when we fall victim to the Planning Fallacy, our squads still ship high-quality work that will deliver value for Todoist and Twist users, even if it means leaving off some things for a later version.

When you’re going to miss a deadline, communicate that early and often. No matter how careful you are, you will inevitably find yourself with a looming deadline and no chance of meeting it. If you’re anything like me, your first instinct will be to stick your head in the sand and avoid thinking about it (see “Present Bias” below). But that just makes everything worse. The earlier you can let people know, the better they’ll be able to adjust their own plans. Most people are understanding. Even when they’re not, they’ll be a whole lot more understanding than if you told them you’d be missing a deadline after the fact.

More reading if you're interested:

Quantify Yourself: (Mostly) Free Tools & Strategies to Track (Almost) Every Area of Your Life

4. The Sunk Cost Fallacy a.k.a Why we want to finish what we started, even when we shouldn’t

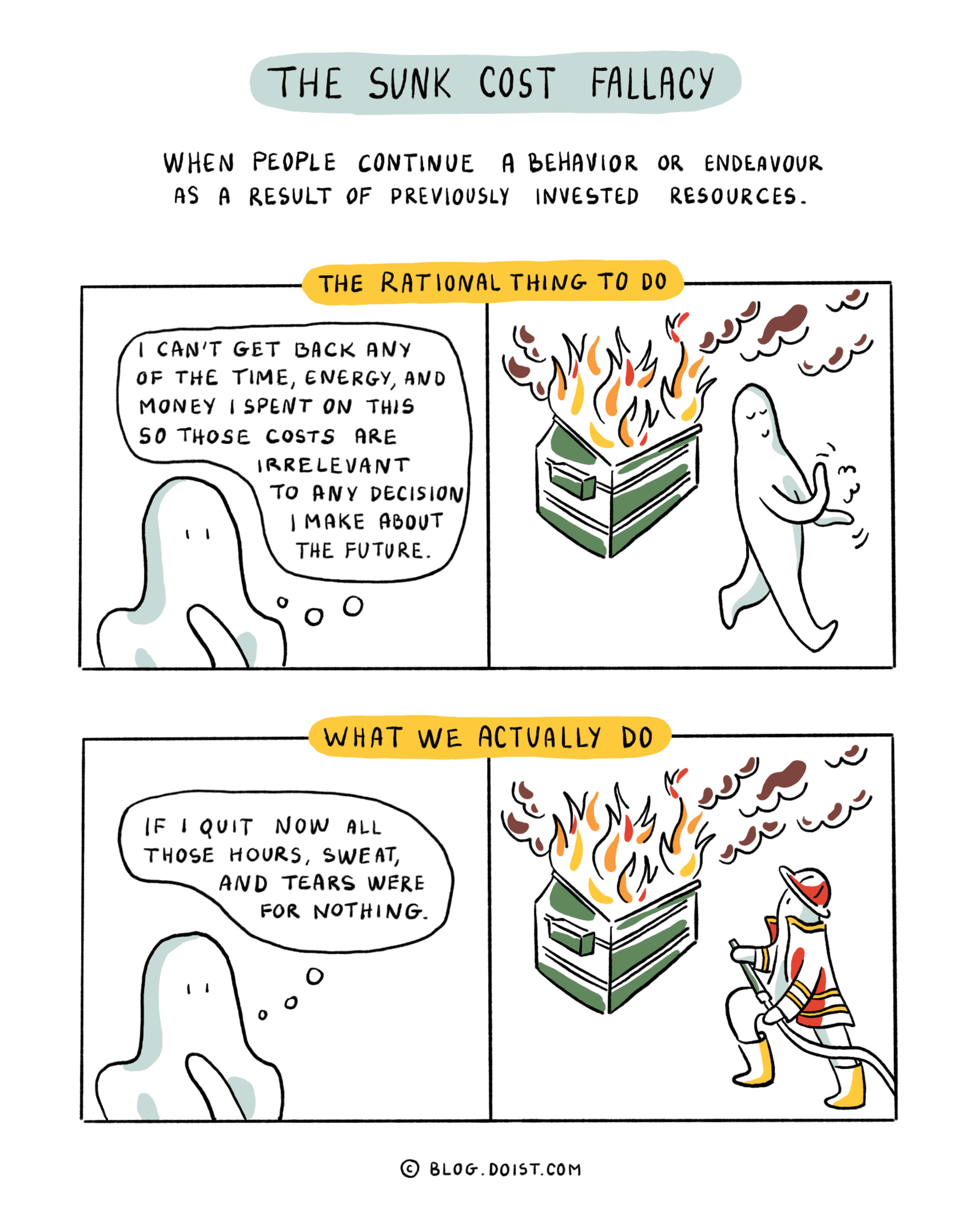

The Sunk Cost Fallacy describes our tendency to continue in an endeavor as a result of past investments in it. Sunk costs are any costs – like time, energy, or money – we’ve invested in the past that we can’t get back. Because there’s nothing we can do about them, the rational thing to do is ignore sunk costs when deciding how to invest our future time, energy, and money.

In reality, we feel compelled to press on in order to make those previous investments “worth it”. We continue to pour more money, time, and energy into the commitments we’ve started even when our limited resources would provide better returns elsewhere. To make matters worse, society tells us the Sunk Cost Fallacy is a virtue. We’re told that quitters never win. We’re told we need grit and resilience. We equate walking away with failure when it can actually be the most logical course of action.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy keeps us from spending our time well in ways big and small, from trudging through a bad book just because we started it to continuing in a career that makes us miserable because we’ve already invested years of our lives and thousands of dollars on a degree. The fact that you’ve invested one year or two years or even ten years of misery and discontent into a career is not a good reason to continue being miserable for the next three decades. And yet, that’s exactly what the Sunk Cost Fallacy leads us to do.

What you can do about it:

Make opportunity costs explicit. Every decision has two costs. The first is the actual amount of money, time, or energy you invest. The second cost is the benefit you would have gotten from the next best alternative. This hidden price is called the opportunity cost and we’re much more likely to ignore it when we make our decisions. For example, when considering a career change, we tend to focus on the money we’d be giving up. We fail to take into consideration the joy and satisfaction we’re currently missing out on by staying. The first step to counteracting the Sunk Cost Fallacy is making clear what alternative we’re giving up by continuing to invest more time, energy, and money into what we’ve already started.

Do a quarterly inventory of your commitments. We often fail to adjust course because we never reach a crossroads where we have to decide whether to keep going or walk away. You need to create your own decision moments where you take a step back and decide if continuing a goal or commitment makes sense. Set a specific timeline to periodically map out the big picture of where your time is going and where you want it to go. To make the opportunity costs explicit, visualize your time as a pie graph so that you can’t add anything without taking away from something else.

Ask yourself “If I were just starting this endeavor today, would I still do it?”. If the answer is no, then the logical thing to do is cut your losses and walk away. Sometimes, quitters win.

More reading if you're interested:

How to Conduct Your Own Commitment Inventory

5. Present Bias a.k.a. Why we procrastinate, eat junk food, and don’t save for retirement

Those of us who struggle with procrastination are intimately acquainted with the Present Bias.

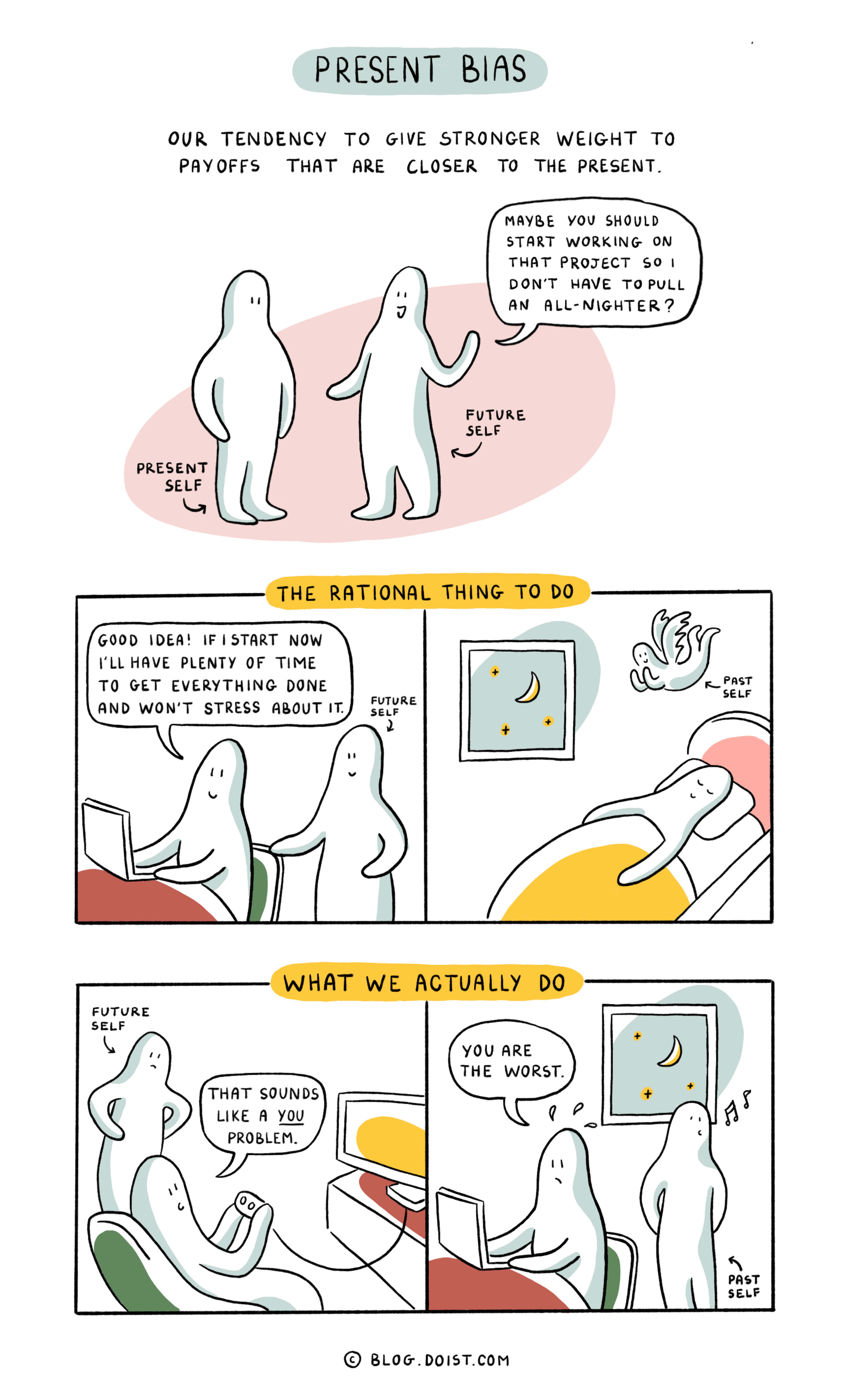

The Present Bias describes our tendency to choose a smaller, immediate reward over a larger reward in the future. Unfortunately, it seems to be an immutable law of nature that the things that are better for us in the long-term are a drag in the short-term. Ice cream tastes better than broccoli. Buying new clothes is more fun than saving money for a far-off retirement. Playing video games is more pleasant than writing or coding or designing.

Present bias leads us to consistently optimize for our current enjoyment, forever putting off the harder things that set our future selves up for success. When we fail to eat healthier, save more, or make progress on our goals, we’re digging ourselves into holes and leaving it to our Future Selves to try and find a way out.

What you can do about it:

Help out your Future Self. If you want to get up and exercise in the morning but have a tendency to hit snooze, you could have all your workout clothes set out the night before and arrange to meet up with a friend for a morning jog. If you want to focus on your work but find yourself doomscrolling Twitter instead, lock yourself out of your social media apps and websites at certain times of the day with a service like Freedom. If you have a hard time saving money, automate your savings withdrawals every month so it happens without you having to think about it.

Find ways to make the “right” thing a little more pleasant. Seek out a form of exercise you actually enjoy. “Bundle” an activity you enjoy – like watching Netflix – with an activity you put off – like folding laundry. Find healthy recipes that are also delicious.

Reframe how you think about rewards. If you can’t overcome Present Bias, find a way to work with it. Instead of running to lose weight in 6 months or writing to become a famous novelist, focus on the feeling of satisfaction you get after running a mile or writing a 1,000 words a day. When it comes to accomplishing goals, research shows that enjoying the process is a far better predictor of success than desiring the long-term outcome.

Imagine your future self. Studies show that taking the time to imagine our future selves can help motivate us to choose longer-term payoffs over immediate gratification. At the beginning of every day, imagine yourself completely satisfied at the end of the day. What one thing have you accomplished? Start on that task first.

More reading if you're interested:

Present Bias: Why You Don’t Give a Damn About Your Future Self

Social Pressure vs Commitment Devices: Which is Better for Behavioral Change

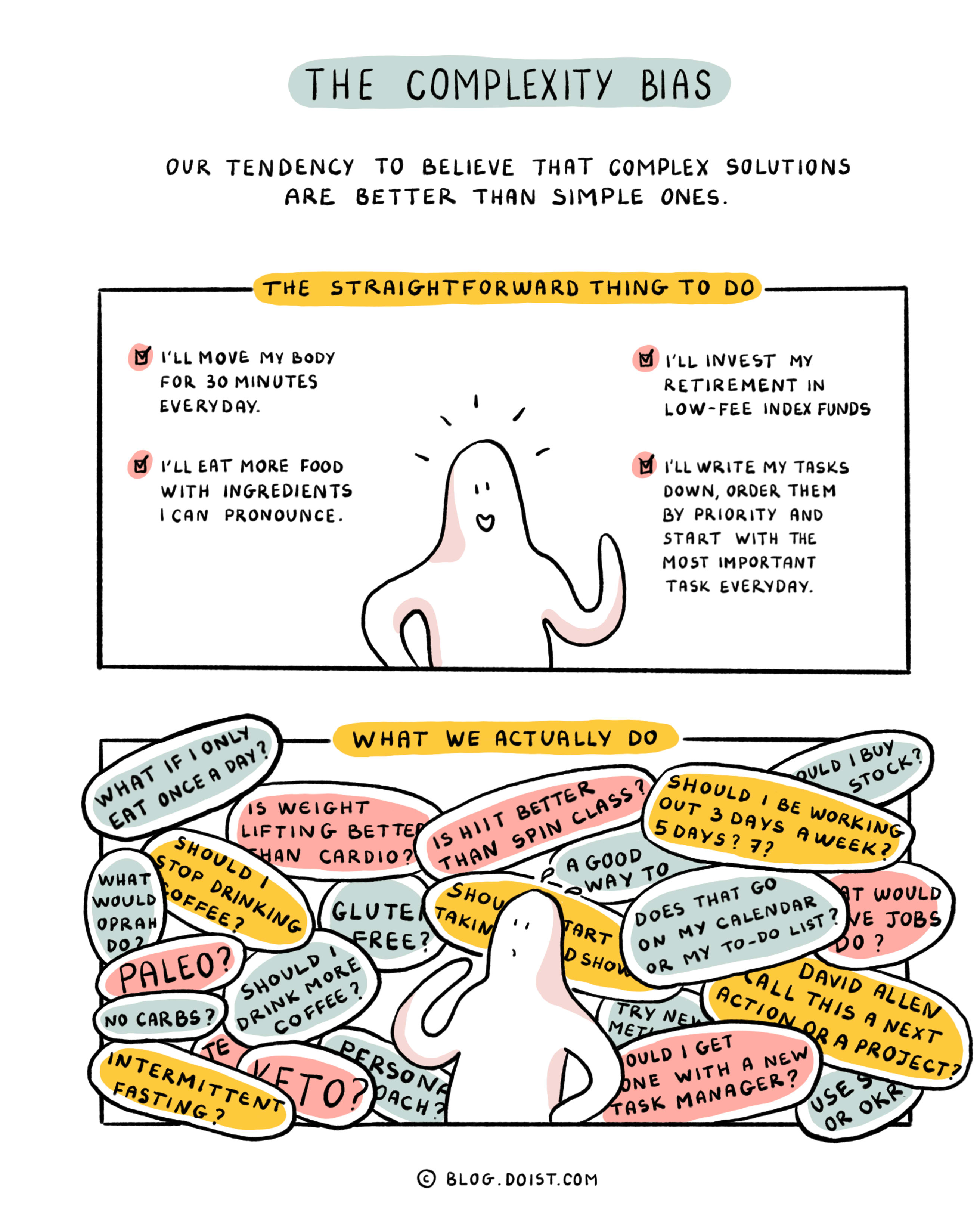

6. Complexity Bias a.k.a. Why we overcomplicate our lives

Why choose a simple explanation when a complex one will do? Complexity bias describes our tendency to prefer complicated explanations and solutions over simple ones.

It’s why we debate the science of intermittent fasting and ketogenic diets instead of following Michael Pollan’s advice to “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” It’s why we pay financial planners to tell us how to save for retirement instead of taking 15 minutes to open a Vanguard account, select an index fund, and set up an automatic monthly deposit. And it’s why we’re drawn to the finicky intricacies of productivity systems like Getting Things Done© instead of simply working on our most important tasks first.

Complexity can keep life interesting, as when we develop complex rituals for making a simple cup of coffee or when we carefully tend our sourdough starters for the perfect loaf of bread. However, complex systems are more difficult to maintain over time. As someone who has tried and failed many times to adhere to the GTD methodology, I swear it feels like the system is actively trying to fall apart.

In addition, the perception of complexity often leads to avoidance. When we think something is difficult to do or understand, we don’t even try. If we believe that organizing our lives requires a complex system like GTD, we’re less likely to experiment with a simpler system we might have a better shot at sticking to. The trick is to embrace complexity when you genuinely enjoy the process, but don’t let the perceived complexity keep you from getting started.

What you can do about it:

Develop a bias for action over research. You don’t have to fully understand a concept to get started. Instead of seeking perfect knowledge at the start, take an iterative approach to your endeavors: Try things, see how they work, and slowly improve over time. It’s the fastest way to learn. Done is better than perfect.

Choose the system you’ll stick with. It may be that intermittent fasting is objectively the best way to burn fat or that GTD is the ideal way of organizing your tasks, but it won’t do you any good if you can’t stick to it long-term. Look for systems that work with your natural inclinations, even if they aren’t the most effective.

Apply Occam’s Razor. Occam’s Razor states that, when faced with two possible explanations for the same evidence, the one that requires the fewest assumptions is most likely to be true. While there are exceptions to every mental model, Occam’s Razor is a good rule of thumb for counterbalancing the complexity bias.

More reading if you're interested:

Complexity Bias: Why We Prefer Complicated to Simple

How to Use Occam’s Razor Without Getting Cut

The Science of Analysis Paralysis & Why It Kills Your Productivity

7. Hedonic Adaptation a.k.a. Why we aren’t happy

Hedonic adaptation is our tendency to quickly return to our normal levels of happiness after both positive and negative external events. We pursue a promotion, a raise at work, a certain number of Twitter followers because that’s what we believe will make us happy. When we reach our goals, we get a temporary bump in happiness, only to go right back to our baseline levels the next week, day, or even hour.

What good is striving for goals if accomplishing them leaves us feeling empty moments later?

What to do about it:

Set many smaller goals instead of one big one. Most of us set big, far-off goals that we’ll only accomplish every once in a long while: graduate college, lose 50 pounds, get the promotion, run a marathon. Go big or go home. We spend a great deal of time pursuing a goal that will only give us a one-time, temporary bump in happiness when we accomplish it. Instead, you can hack hedonic adaptation by setting smaller, more frequent goals to experience more frequent bumps in happiness, even if they’re still temporary.

Enjoy the process, not just the outcome. If you’re a writer, don’t fantasize about publishing a novel. Savor writing it. If you’re trying to lose weight, don’t obsess over hitting a number on the scale. Savor the satisfaction of feeling stronger, fitter, faster with each lift, step, or burpee.

The outcome won’t make you happier, but the act of showing up every day can. If you don’t enjoy the process, it might be that you were pursuing the wrong outcome in the first place.

Pursue strong social connections. While happiness from promotions and raises is fleeting, studies that follow people over many decades show that strong relationships with others – family, friends, or broader community – is the strongest predictor of long-term happiness and health.

By all means, pursue big, ambitious goals, but don’t neglect the people who will celebrate with you when you achieve them.

More reading if you're interested:

The Surprising Science of Happiness [TED Talk]

Are We Trading Our Happiness for Modern Comforts?

Once you learn about these cognitive biases you can’t help but see them everywhere. Unfortunately, it’s easier to recognize these mental errors in others than it is to see them in ourselves. We have a cognitive blind spot when it comes to our own cognitive biases.

Being aware of these mental traps is a good first step, but it’s not enough to keep us from falling into them over and over again. We need to put in place habits, systems, and mindsets to short circuit the cognitive biases our brains are hardwired to follow. While we may never be completely rational beings, we can set ourselves up to make better decisions about our time more of the time.

Comic artwork by Doist designer Anaïs Pirlot-Mares 🎨